Crackle is an incredibly versatile style of weaving from a design perspective, allowing you to weave anything from intricate diamond patterns to chunky geometric shapes.

But even though it can create some pretty fancy designs, crackle makes cloth that has substantial body and stands up to wear and tear. Crackle has us dreaming of beach towels, picnic blankets, decorative throws, and--of course--sewing up some beautiful tops from handwoven cloth.

With so much going for it, why isn’t everyone weaving crackle? Well, it has a reputation for being a little… complicated. But while the threading patterns can be pretty complex (often with dozens of ends in a pattern repeat) the wide range of treadling options mean you can set your own challenge level with crackle. Once you’ve tackled the threading, you might want to take on a treadling challenge like weaving the pattern as drawn in, or you might find using simple point twill treadling is more your speed. Either option will produce a beautiful result.

So ok, I think that crackle is super exciting and you should definitely take a risk on trying it out. But what is crackle weave?

Crackle weave is a bit like a cross between overshot and summer-and-winter. Like both of these styles, crackle uses two wefts: a heavier pattern weft that shows off the design, and a thinner ground weft used to provide stability. And like overshot and summer-and-winter, crackle patterns are written by combining different patterns blocks (set threading repeats with specific rules).

What makes crackle distinct is that the threading blocks are made up of little point twill sequences. You’ve likely seen 4-shaft point twill, with the threading going 1-2-3-4-3-2-1. This is a common threading used to make zigzags and diamonds. Crackle uses the tie-up for 2/2 twill, but the point twill used for crackle is a little simpler. This is because crackle only uses three shafts at a time--for example, 1-2-3-2-1.

Three-shaft point twill on its own looks like this.

So here’s where it gets cool.

On a four shaft loom, you can make four different 3-shaft point twill sequences. You can start on shaft one for 1-2-3-2, on shaft two for 2-3-4-3, on shaft three for 4-3-1-4, or on shaft four for 4-1-2-1. These are the building blocks of crackle weave.

From right to left, these are Blocks A, B, C, and D.

Block A = 1-2-3-2

Block B = 2-3-4-3

Block C = 3-4-1-4

Block D = 4-1-2-1

On their own, these threadings are very simple. But when you start stringing them together, you create ripples and mountains.

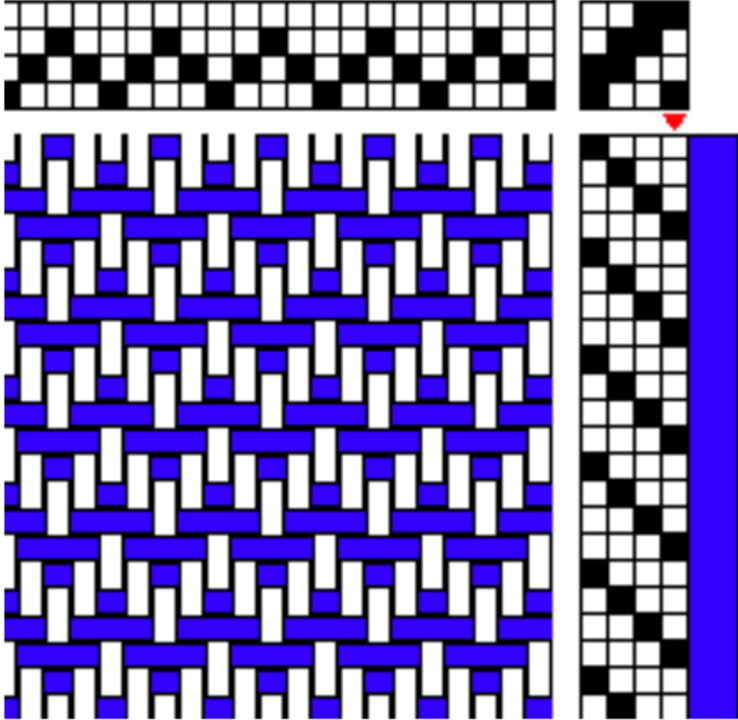

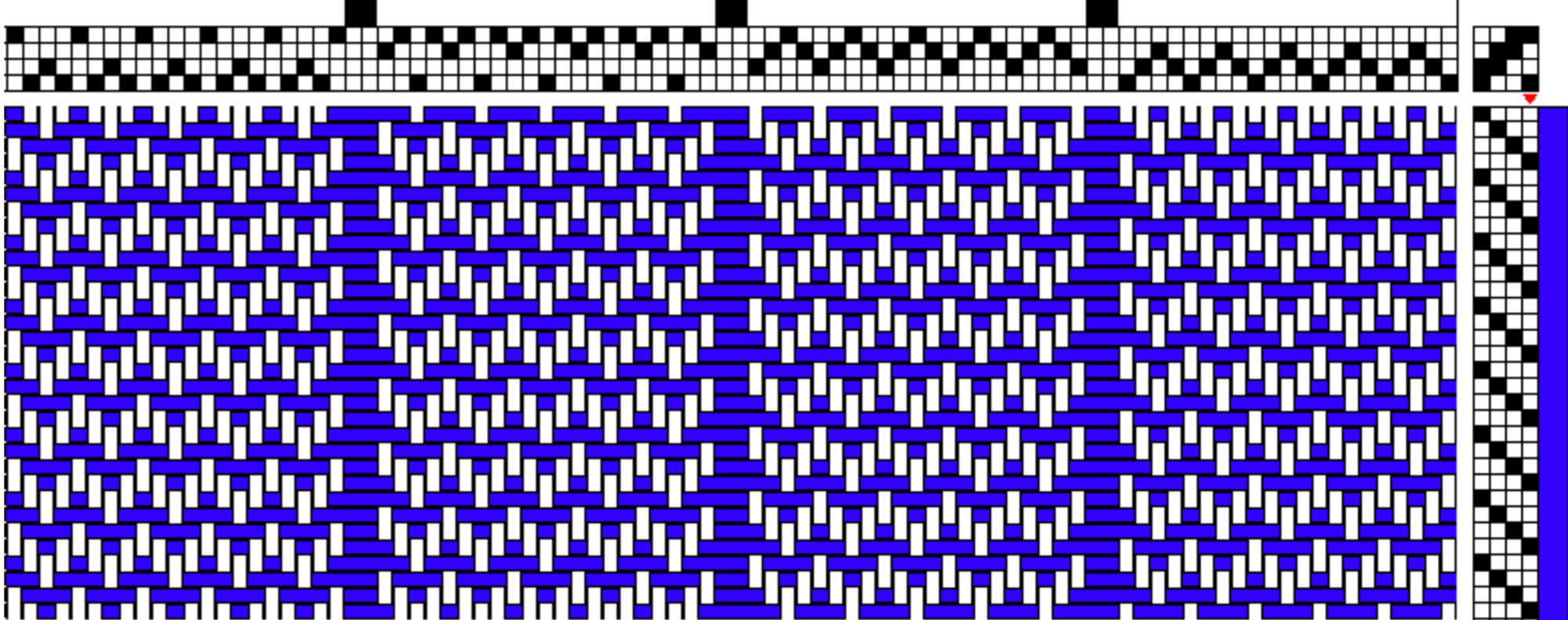

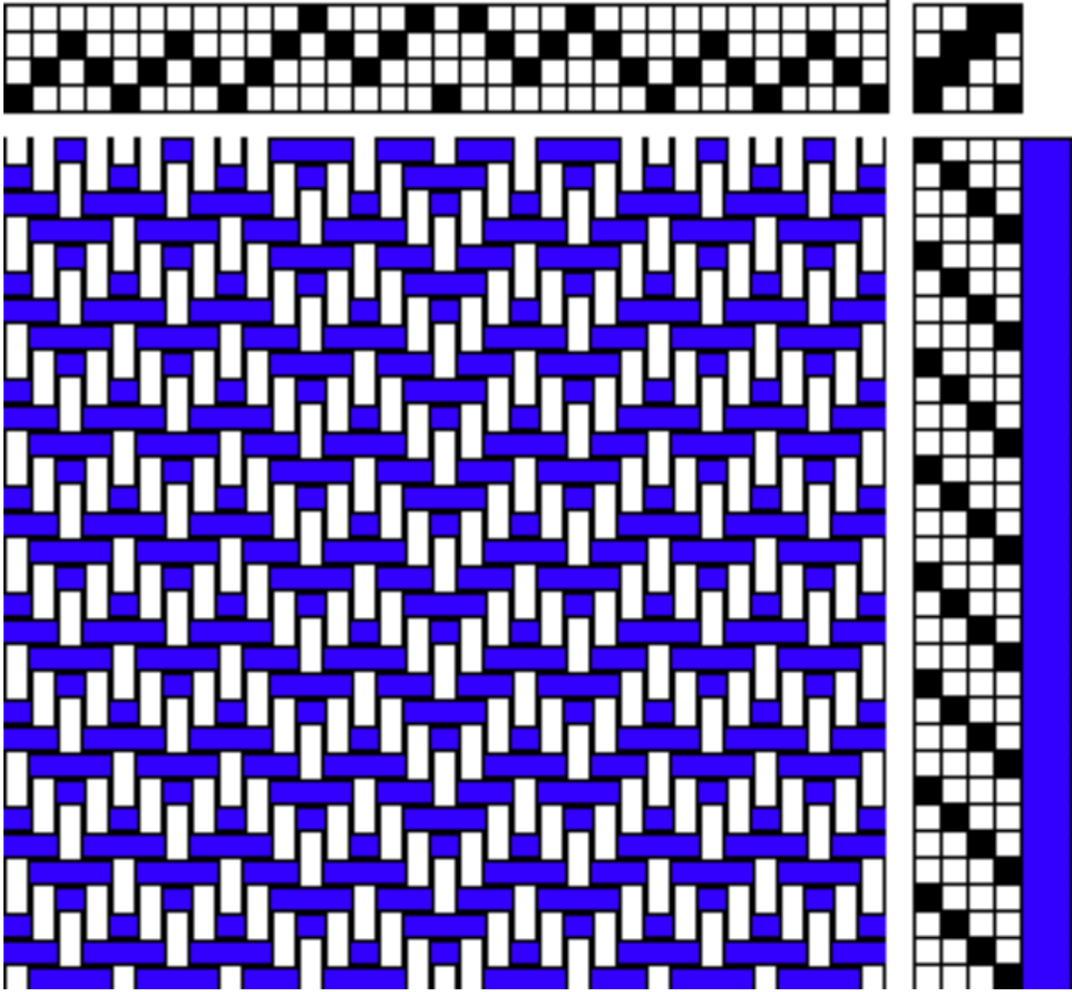

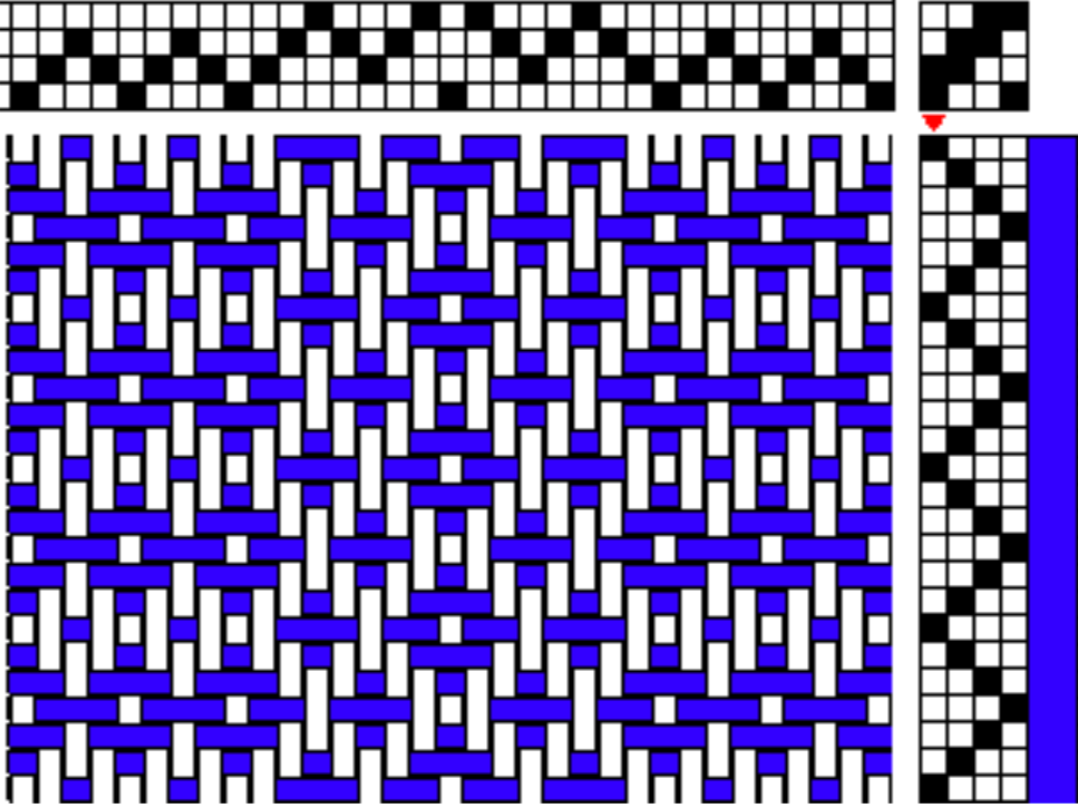

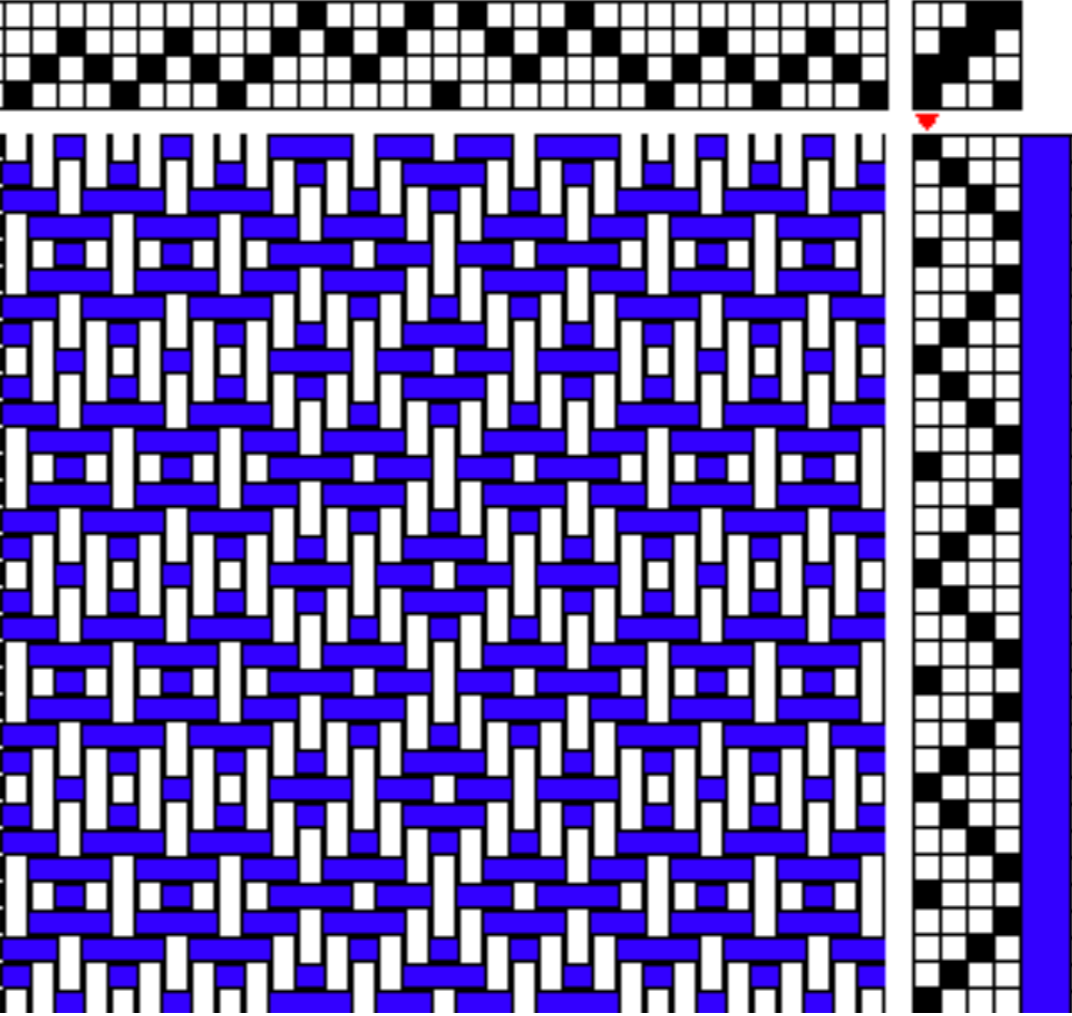

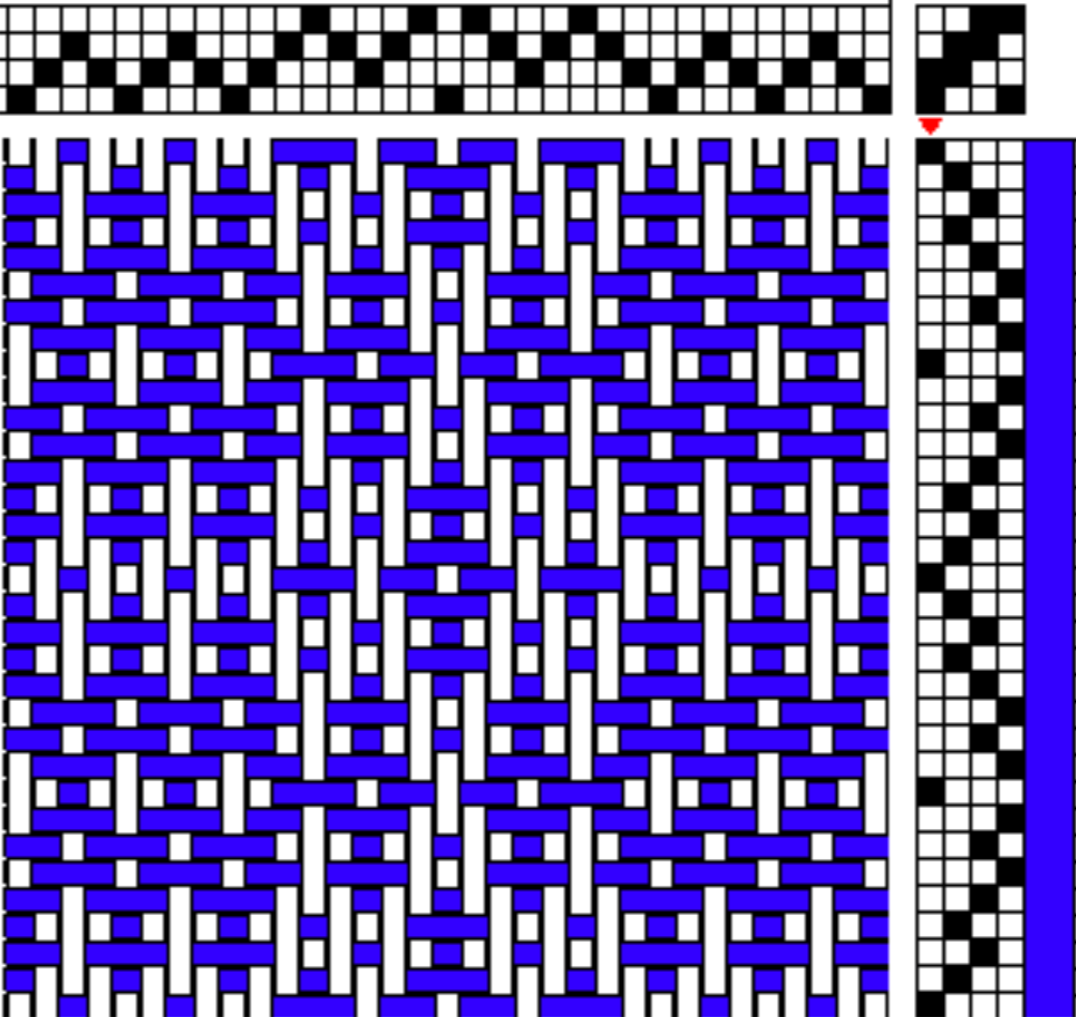

Throw some different treadling on those ripples and you can make interlocking fields of diamonds….

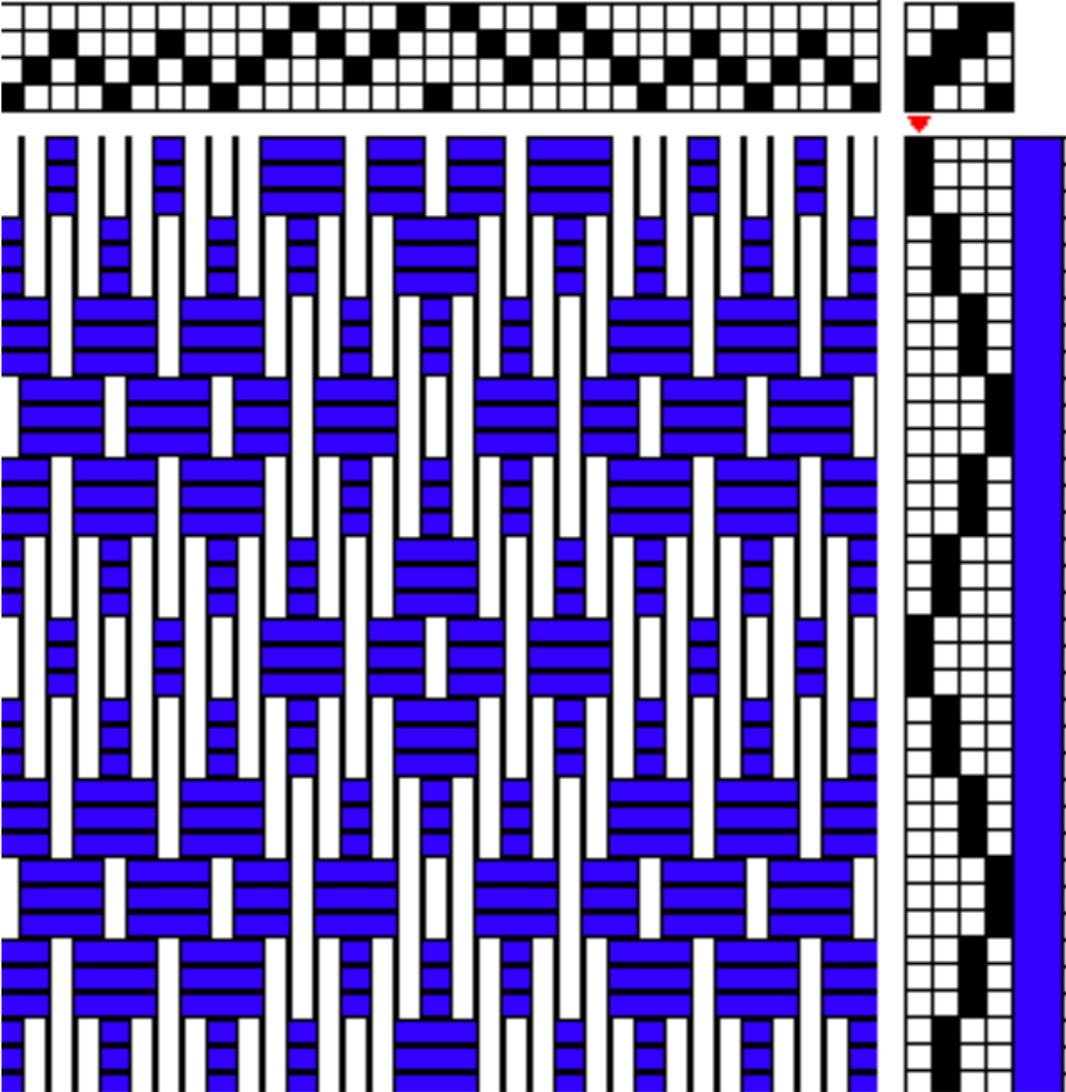

...or bold geometric blocks....

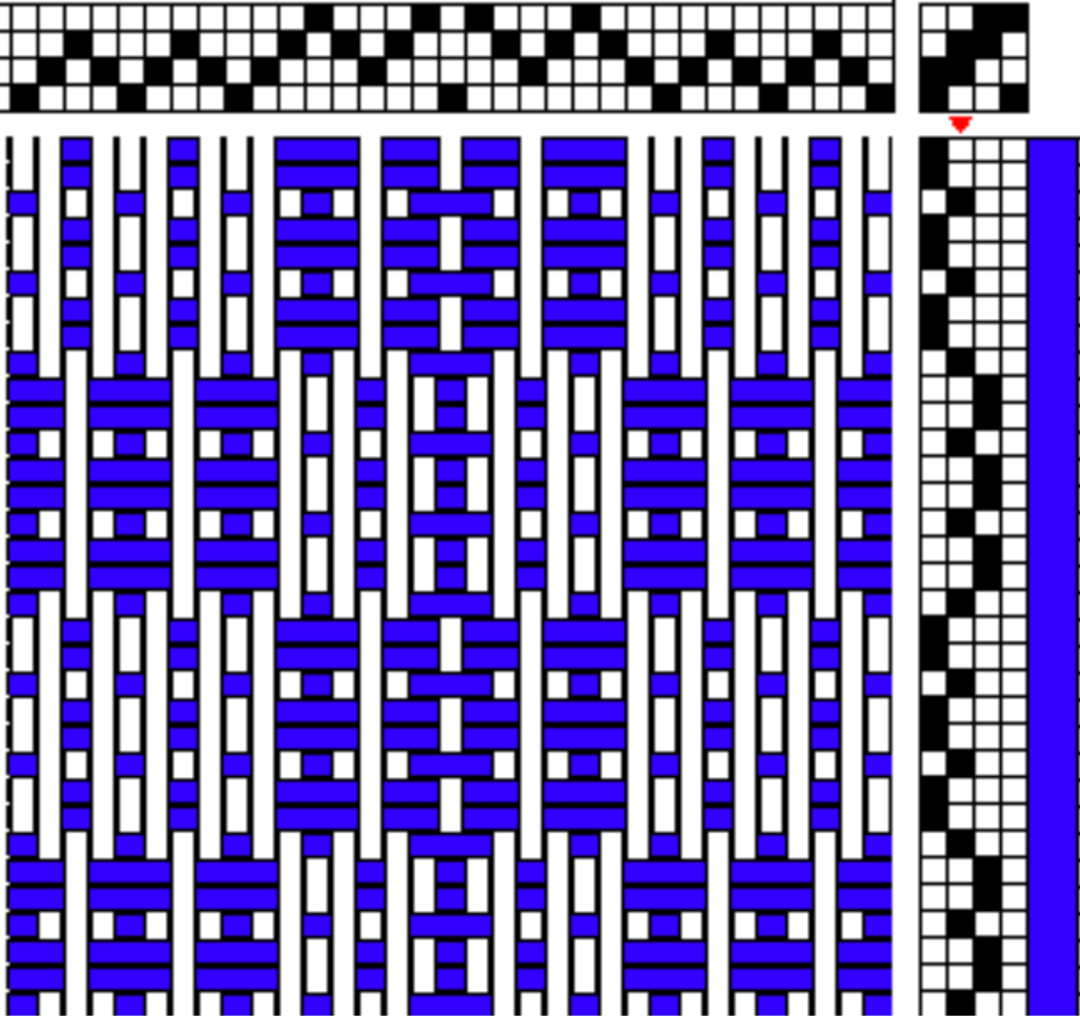

...or some of the most intricately detailed designs you can produce on four shafts.

It is mindblowing what a diverse range of designs you can get from a single crackle threading!

And because the foundation is a small point twill, the floats stay small. All of the above drawdowns have a maximum float size of three, making all of them suitable for practical application. Wide open design options AND cloth that won’t snag? Crackle is remarkable.

If you really want to dive into the nitty gritty, here’s how the designs come together.

You can repeat a block as many times as you want in a crackle threading. Whenever you move from one block to the next, close off the block by returning to the first thread in that block. So to move from Block A to Block B, you would wrap up Block A with a 1 before beginning Block B: 1-2-3-2-1-2-3-4-3. (Some weavers also simply eliminate the duplicate between the end of Block A and the beginning of Block B: 1-2-3-2-3-4-3. Either is fine! If you look at the drawdowns above you’ll see I used a mix of both strategies.)

Because crackle depends on smooth transitions between pattern blocks, you can’t just skip straight from say, Block A to Block C. Crackle patterns wander up and down and all over, but they only ever move one shaft at a time. They never skip a shaft. This ensures a stable cloth with small floats. So if you want to go from Block A to Block C you can still do it, but you need to connect them with extra threads called ‘incidentals’. The rule for crackle is this: every time you skip over a block, add the first thread of that block as an incidental. So to move from Block A to Block C, you would thread Block A (1-2-3-2), wrap up Block A by returning to its first thread (1), then add the incidental for Block B (2), before moving to Block C (3-4-1-4).

Or put all together: 1-2-3-2-1-2-3-4-1-4.

See how the extra threads smooth out the path from one block to another? You’d be amazed how quickly these incidentals become second nature once you start playing around with crackle designs.

But if everything between my descriptions of pretty fields of diamonds and this part sounded like absolute nonsense, don’t worry! You can still enjoy weaving crackle!

While many crackle project call for more complex treadling (treadling in blocks, as drawn in, as summer-and-winter, as overshot, or in pairs) this is not required. All of the fussy stuff goes into designing the threading. If you have a pattern that provides a threading, literally any standard twill treadling will work with any crackle pattern. You can do straight twill, point twill, extended point twill, advancing twill, rosepath, Ms & Ws, or even Wall of Troy treadling, and something beautiful will result! The only tricky part is remembering to add tabby (plain weave) picks with your ground weft in between each pick of your pattern.

That said, you can weave crackle without adding tabby if you want. You’ll miss out on the extra body that using a pattern and a ground weft provides, but the floats are short enough that you will still get stable cloth.

This is the magic of crackle weave. Once the threading is set, you can do almost anything to it and get a pleasing result. Crackle is the ultimate weaver’s playground.